The F Word

It’s on the tip of everybody’s tongue – so why aren’t more people saying it?

We’re all thinking it, but an awful lot of people still aren’t quite willing to say it with their chests. There’s a fog of denial shrouding the topic. We murmur and whisper about it, refer to it obliquely, change the topic when people enter the room, as though it were some kind of shocking obscenity that ought not to be mentioned in polite company.

People are snatched off the streets by masked men on no other pretense than the colour of their skin. “Horrible,” we say. Trans people are vilified as terrorists, are blamed for every societal ill, are suspected of every act of political violence, have their rights stripped away from them. “Shocking,” we say. The news media comes under sustained and intense pressure to silence critics of the government and fall into line with the administration’s narratives. “Worrying,” we say. The president directs the national security apparatus to investigate anybody who holds anti-capitalist views or opposes “traditional American views on morality”. “Alarming,” we say.

Fascism, I say, and I say it loudly, and I say it again: fascism. It’s fascism and it’s here now and it’s growing more powerful and it’s not going to go away just because we’re unwilling to acknowledge the problem for what it is, which is fascism.

The fascists object to this kind of directness, labelling it dangerous rhetoric from far-left radicals that encourages and enables political violence. This is, like most things that fascists say, emotionally manipulative bullshit. They are trying to take a powerful tool out of our hands with alarmist trickery. They are trying to distort reality and make us question our judgment. They are trying to rhetorically transform the victim into the offender. We can’t let fascists’ feelings get in the way of telling the truth.

If they’re trying to appear more reasonable and conciliatory, fascists may also object to being called fascists on definitional grounds. “What is fascism, anyway?” they’ll demand, and perhaps imply that the people calling them fascists are the real fascists. This is a bad faith question coming from a fascist’s mouth and doesn’t deserve a serious response. In this essay, I’ll be offering three definitions of fascism: a short one, a long one, and an insult. We’ll start with the insult, which is the one I recommend offering to fascists in lieu of substantive debate and discussion: fascism is a highly contagious species of paranoid brain worm. Don’t spend too long talking to fascists, or you too might get infected by it!

Getting drawn into a debate with a fascist about whether or not he’s a fascist is one of the most pointless conversations that one could ever be involved in. Generations of anti-fascist organizers insist that you shouldn’t get in arguments with fascists. Fascists will make you twist yourself into knots trying to define your terms, and then ignore anything substantive you have to say, all while using the opportunity to make their positions appear more legitimate to uninformed observers.

If a fascist tries to debate you, don’t engage. There is nothing to be gained from discussion with them, no matter how heartfelt or well-informed or persuasive you are. I deeply wish that this weren’t true, that we could reason with fascists, but decades of experience to the contrary shows that it’s a losing battle. Fascists need to be shouted down and kicked out, not treated as though they’re just uninformed and misguided.

This essay is not directed at fascists. If you suspect that you might be a fascist and are reading this, go away and reflect on why you’re unwelcome in so many spaces. This is for the rest of us, watching the ascendancy of fascism in real time and trying to figure out what the hell we’re going to do about it. I don’t have a complete answer, but I do have a partial one: we have to use the power of the word “fascist” against them, and in order to do that, we all need to get a lot more comfortable calling fascism by its name.

The word “fascism” is admittedly a slippery one. The semantic confusion surrounding the word is actually one of modern fascism’s greatest strengths. When Trump first became President, a chorus of experts cautioned against the use of the word to describe the MAGA movement’s leader. They conceded that he had strongman authoritarian tendencies, displayed an uncomfortable willingness to cozy up to neo-Nazis and white nationalists, showed scorn for democratic norms, and deployed classically fascist tropes about reversing the decline of the nation, but they insisted that other key components of fascism, such as a violent paramilitary movement and the suspension of rights, were absent. Today, amid massive increases to the ICE budget and growing assaults on the freedom of speech, many of those same experts are now fleeing the United States. While we debate over whether the label can be applied, the fascists escalate and entrench their power.

But why is it so hard to see modern fascism for what it is? Historical illiteracy is probably one of the biggest obstacles. Put simply, most people don’t have even a cursory knowledge of the tenets of fascism or the factors that drove its horrifying rise in the 1930s. Instead, most people rely on an intuitive understanding of fascism defined by two vague characteristics: aesthetics and evilness.

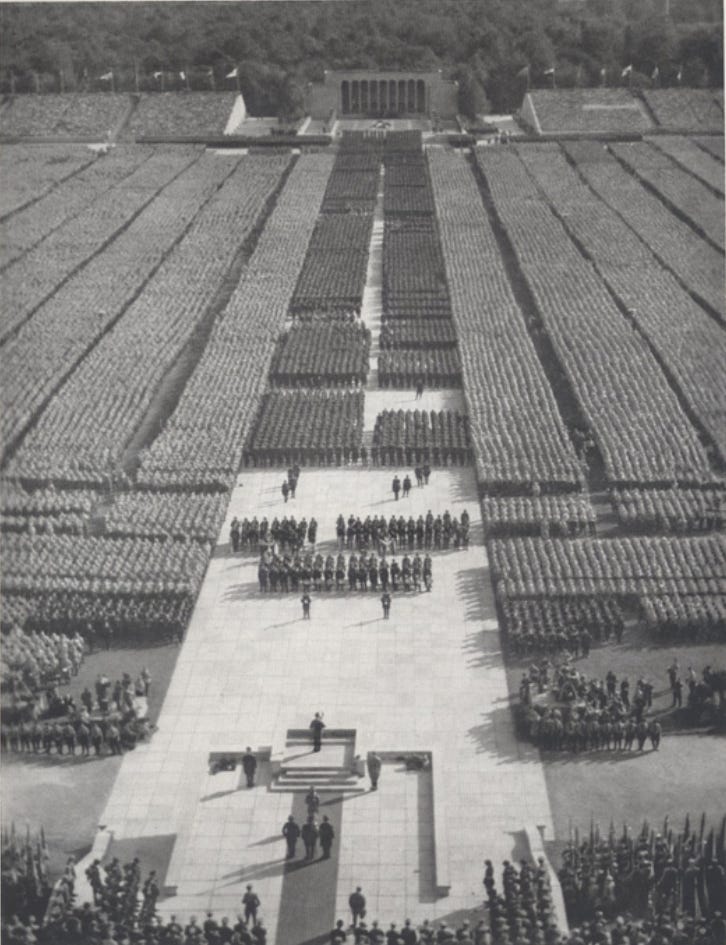

Our modern understanding of fascism is understandably Nazi-centric. The visual spectacle of the Third Reich at the height of its powers made for compelling and enduring imagery – the red-white-and-black banners, the iconic Hitler moustache, the sharply dressed jackbooted soldiers, the straight-arm salutes. We’ve all seen pictures of Hitler speaking to adoring crowds of hundreds of thousands:

When we picture fascism, what we picture is this kind of fascism: fascism at its most entrenched, fascism after it had seized and consolidated power. This ubiquitous historical imagery has created a kind of phantom archetypal image in our imaginations of The Fascist which maps very imperfectly onto modern fascist movements. We’re far more likely to feel comfortable pointing out fascism when it has all of the visual trappings of Nazism, like the loser white supremacists who are still cosplaying as Nazis today, seig heiling and wearing swastika armbands and signaling their worshipful attitude toward Hitler with their weird little dog-whistle coded messages. That particular brand of fascism is easy enough to recognize. When the distinctive aesthetic (and the open statements of white supremacy) are absent, though, most people feel a lot less confident calling a fascist a fascist.

What’s more, for most of us, the fascist hasn’t really been a presence in our daily lives until relatively recently, so they’re easier to think of as cardboard-cutout bad guys. In popular media, Nazis have long been depicted as absolute evildoers, mindlessly intent on doing evil for the sake of evil. Why they’re so evil, what their motivations for evil deeds are, how they became so evil – these questions are largely unexplored. In the popular Western imagination, the fascist is a kind of historical boogeyman, a categorically wicked monster, a comic book villain, an uncomplicated force of pure malevolence and destruction. All our lives, we’ve been presented with a flattened picture of fascism, reduced to its aesthetics and its hatefulness. The good guys beat the Nazis and we all cheer. We leave the theatre with a warm glow in our stomachs.

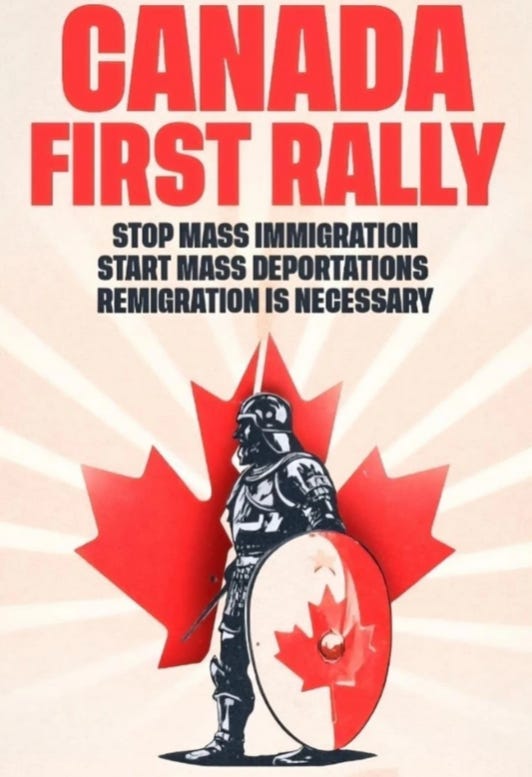

This two-dimensional mental image of fascism has prepared us poorly for the current historical moment. This is what fascism looks like right now in Canada:

These are images from the “Canada First Patriot Rally”, an anti-immigration fascist assembly held on September 13 at Christie Pits in Toronto. This choice of location was a deliberate provocation. Christie Pits is not a typical protest site; it’s a medium-sized park in a fairly quiet neighbourhood west of downtown. I can’t recall there ever being a major rally held there in all the years I’ve been living in Toronto. Christie Pits was, however, the site of Canada’s most infamous race riot in 1933, an hours-long violent brawl instigated by members of a local Swastika club who targeted young people in the immigrant neighbourhood around Bloor and Christie, particularly Jewish teenagers.

The modern incarnation didn’t feature any swastikas that I saw, but its theme was essentially the same. Dubbed the “Canada First Patriot Rally”, the event was promoted online with cryptic captions like: “This is the time for true Canadian patriots to stand together. Our country is changing fast and not for the better. If we don’t fight for what we have, we will lose it.”

In many of their statements, event organizers pretended that they were just trying to have an open and honest discussion about the details of Canada’s immigration policy. However, like most things that fascists say, this was emotionally manipulative bullshit, directly contradicted by their own words. Promotion for the event also included Crusader imagery and openly white supremacist slogans:

To be clear about what we’re looking at, “remigration” is a euphemism for ethnic cleansing; proponents of remigration envision the relocation of all non-white foreign-born residents and their “unassimilated” descendants back to their ancestral country of origin, regardless of their citizenship or legal status, either voluntarily or through force. A common remigration slogan among Canadian fascist Twitter users is “They all have to go back.” The idea was relegated to the fringes of white nationalist movements just a few years ago, but it’s gone mainstream with unnerving speed; in May, Donald Trump proposed the creation of an “Office of Remigration” within the State Department.

These new Canadian fascists aren’t making an effort to hide their fascist agenda. But there’s still a lot of reluctance to name the problem. The media avoided using the word “fascist” to refer to this provocative gathering, preferring to describe attendees as “far-right” or “anti-immigration”. There was even some mushy both-sides-have-a-point coverage, like this CP24/City News segment, which allowed the event’s organizer, Joe Anidjar, to present himself in the most reasonable terms possible:

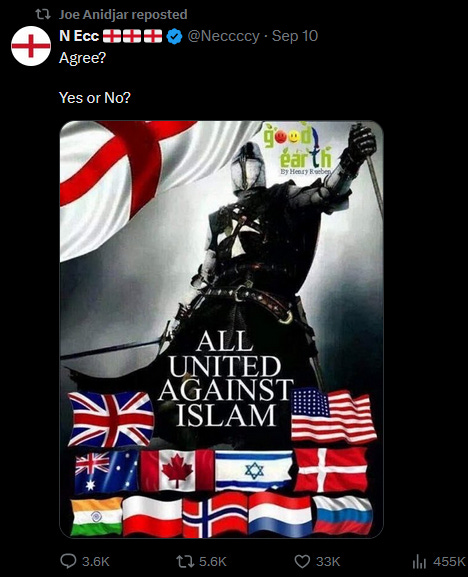

In a cozy interview with Ben Mulroney on 640 AM, Anidjar vociferously denied being a fascist, a Nazi, or a white supremacist, and made a point of saying repeatedly that he’s not against all immigration. Mulroney didn’t dig into his actual beliefs too deeply or press him on what kind of immigration he is against, but a quick look at Anidjar’s Twitter feed tells the story pretty clearly:

These are unequivocally fascist slogans and positions, but the news media is treating this rally and this movement as an unremarkable news story and the strong denunciations of it by migrant groups and leftist organizations as overreactions. Seeing fascism presented so mundanely has a pacifying effect on our fight-or-flight responses, making us question whether we’re unreasonable for being alarmed.

It’s already hard enough to call fascism what it is, because these goons don’t look like archetypal fascists. We need to dispel this confusion. It’s absurd to think that modern fascism would faithfully replicate the aesthetics of its earlier incarnations. A fascist movement at the height of its powers will necessarily look and act differently from a fascist movement on the rise that still faces substantial opposition, just as 21st-century fascists in a multicultural settler-colonial nation are necessarily going to look and act differently from early-20th-century fascists in a far more monocultural imperial core. We have to stop looking for movie-villain Nazis when we look for fascists. The fascists among us look like people we’ve known our whole lives; in many cases, they are people we’ve known our whole lives.

A second confounding factor is the presence of quislings in modern fascist movements in far greater proportions than has been typical historically. A quisling is a very particular type of fascist, one who betrays their own people in the hopes of benefiting from fascist power. Vidkun Quisling was a Norwegian politician who led a failed pro-Hitler coup attempt in the midst of a Nazi invasion. Quisling was rewarded for this boot-licking behaviour when he was installed by the Nazis as a puppet Prime Minister after their eventual conquest of Norway. He hoped to use his unyielding support for Hitler as a bargaining chip to gain Norwegian independence, although his schemes ultimately and predictably led to nothing. His name quickly became synonymous with the short-sighted treachery he typified. The Times of London celebrated the coinage in a famous editorial: “To writers, the word Quisling is a gift from the gods. If they had been ordered to invent a new word for traitor...they could hardly have hit upon a more brilliant combination of letters.”

There is unfortunately no shortage of quislings today, and this can confuse our ability to identify fascists. For instance, fascism has traditionally been strongly associated with in violence against queer communities, the promotion of the patriarchal nuclear family, the absence of women from political leadership, and white supremacist racism. As a result, when we look for fascists, we tend to look for straight white men. However, things are not so straightforward; for instance, Alice Weidel, co-leader of Germany’s neo-Nazi party Alternative für Deutschland, is a lesbian, and the most successful fascistic politicians in western Europe, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and French President-in-waiting Marine le Pen, are both women as well. Similarly, at the fascist rally in Christie Pits, there was a small but notable contingent of fascists of colour and even some immigrants; Anidjar himself is part Moroccan.

There’s plenty of room for “the right kind of” queer person, woman, or ethnic minority in Western fascist movements – at least for now. Quislings like these are useful to fascism because they provide plausible deniability against charges of racism, sexism, and queerphobia and make fascist movements appear more reasonable. Whether this narrow pluralism is a temporary aberration that will fade away as fascists consolidate power or whether it’s a permanent alteration in fascist ideology in response to generational shifts in attitudes on gender and multiculturalism remains to be seen, and isn’t worth wasting time arguing about in my opinion. The point is that these movements are putting forth openly and violently racist policies and show every intention of following through on them if given the chance. There’s no amount of diversity within fascist movements that would make those positions acceptable.

The question of why these quislings are attracted to fascist movements to begin with is similarly of little interest to me. Fascism, after all, is a highly contagious species of paranoid brain worm, and even those whom fascism ultimately aims to victimize or destroy are susceptible to it. None of us are immune to propaganda – yet another reason that you shouldn’t engage in discussion or debate with fascists.

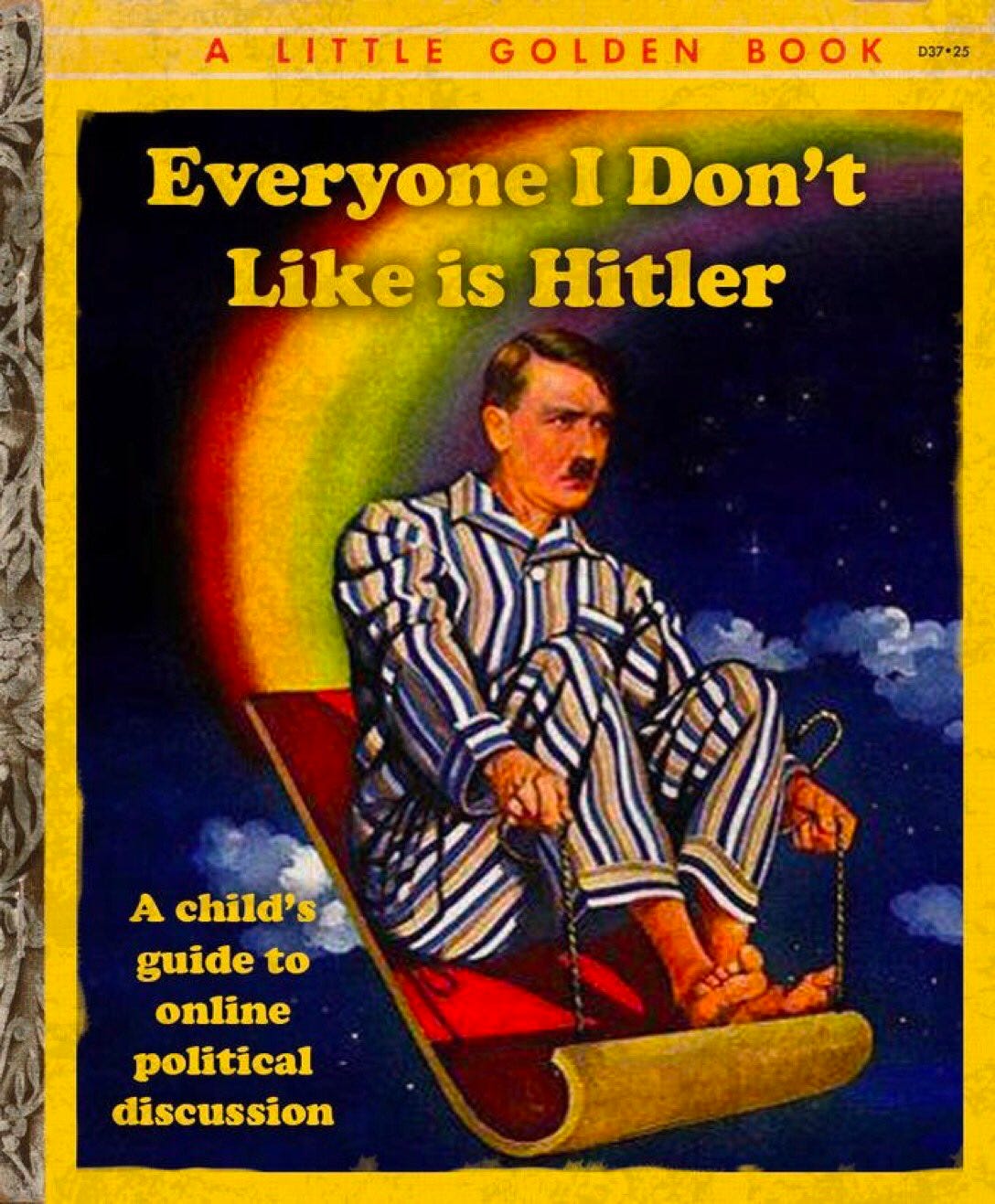

A final component in our collective inability to call fascism by its name is the Boy-Who-Cried-Nazi problem. As the word “fascism” was gradually stripped of its ideological specificity and reduced to a simple Hollywood synonym for “evil”, baselessly accusing one’s opponents of being fascists became a commonplace tactic in arguments across the political spectrum. Mike Godwin observed this trend on the early Internet’s bulletin boards and coined Godwin’s Law in an attempt to point out the shallowness, historical ignorance, and sheer stupidity of many of these analogies to the Third Reich: “As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches one.” Some discussion forums even enforced a rule that as soon as someone made a Nazi analogy, the conversation was over and the person who made the comparison would be considered the loser of the debate. The legacy of Godwin’s Law is that accusations of fascism are automatically illegitimate in many people’s eyes; calling somebody a fascist can be a disqualifying argument, and it has the potential to make you look like a hysterical alarmist.

Nothing could slow the tide of empty accusations of fascism, though. Jewish novelist Shalom Auslander has written about how the word “Nazi” has been cheapened almost to the point of meaninglessness. He describes how the word went from a rarity to a commonplace while he was growing up in the 1980s:

Someone might have been a bigot, or a Jew-hater, or, when it was really serious, an antisemite. But only a Nazi was a Nazi...And then something changed. Suddenly, it seemed, everyone was a Nazi. Jesse Jackson was a Nazi. David Bowie was a Nazi. The president of the United States, whoever he was, was a Nazi, a Nazi whose Nazism was defended by what people in my community often referred to as “The New York Nazi Times”...I gasped when I first heard it used so cavalierly; something holy had been profaned.

I could certainly be accused of committing the same sin, of disrespecting the memory of the victims of fascist atrocities by mentioning a bunch of assholes in MAGA hats in the same breath as the Gestapo. I could be charged with violating Godwin’s law, of taking an analogy too far, of catastrophizing. I understand this perspective, but I disagree. Specious accusations of fascism may be made far too frequently, but fascists are unfortunately no longer a rare thing to encounter in the world. (Godwin himself is now on the record comparing Trump to Hitler.) The power and influence of what is still euphemistically called the “far right” continues to skyrocket, and we have to collectively get our shit together and figure out how we’re going to defeat them. Surely the first step to doing that is recognizing the nature of the problem that we’re facing. It’s not “the alt right” or “populism” or “the MAGA movement” – it’s fascism, and we need to be willing to name it openly.

But it’s fair to ask again, what exactly is fascism? How can I feel so confident in using this word when it’s been so frequently and widely misused? Now that we’ve explored the reasons behind the confusion surrounding the term, its meaning is worth examining in some detail. I want people to be able to know fascism when they see it – to know it, not just to suspect it – and to feel empowered to call it by its name with confidence. So since we’re a few thousand words into this essay and any fascists who may have clicked on it have long since stopped reading, let’s dig into the particulars of what fascism actually is.

Understanding the essence of fascism is easier said than done. Scholars of fascism have struggled to provide a precise and concise definition of this slippery ideology for nearly a century; one famously compared attempting to define fascism with “trying to nail jelly to the wall”.

The main issue with most definitions of fascism is their long-windedness. One of the most popular such definitions is Umberto Eco’s, which lists fourteen different characteristics of fascism; other experts include as many as nineteen. Still others make distinctions between national “flavours” of fascism, leading to a dizzying array of conditionals and historical tangents. Few actual fascists know or care about the contents of these definitions, because at its heart fascism is based on vibes, not theory. Fascism is incoherent by design, and in fact it draws strength from its incoherence. It makes no effort to be internally self-consistent. Fascists are eternal victims and eternal conquerors, violently paranoid and boastfully self-aggrandizing, struggling against an enemy that is simultaneously all-powerful and pathetically inferior.

The key to understanding fascism is recognizing that it’s not an ideology in the traditional sense. Ideologies typically try to proceed logically from first principles to policy conclusions based on observations of reality. All ideologies are part belief and part empirical methodology for understanding the world and approaching political problems. Consider fascism’s natural enemy, communism. Theories of communism start from a few basic ideas – the labour theory of value, the antagonistic relation between economic classes, a historical materialist view of history – and build an edifice of logical conclusions and positions on that basis. Communist theorists refine their approach over time in response to changes in the conditions that they face, with Lenin editing and updating Marx, and Mao editing and updating Lenin. You can agree or disagree with their conclusions, but you can always trace how they got there from their assumptions.

When communists argue among themselves, they tend to argue about theory; when fascists argue among themselves, it’s almost always about tactics. Rather than being an ideology, fascism is a highly contagious species of paranoid brain worm, and those infected by it have little interest in empiricism and logic. It’s driven by distorted, simplified patterns of thought that are in many ways delusionally detached from reality, which makes it both resilient to external challenges and extremely slippery to wrestle with and pin down.

With this in mind, my own attempt at succinctly nailing jelly to the wall focuses less on what fascists think and more on how they think:

Fascists are conspiratorial and irrational thinkers whose beliefs are rooted in emotions rather than facts. They claim to be defending the nation and its people from existential threats and working to restore a mythic past greatness. However, the primary goal of all fascist movements is to constantly expand and consolidate their power by any means necessary.

I believe that this definition successfully encompasses the key aspects of the fascist worldview, describing movements as disparate as the Nazis at the height of their power and the roughly three hundred flag-waving dipshits who tried to take over Christie Pits for an afternoon, while excluding other varieties of conservatism and authoritarianism. This broad applicability comes at the expense of a lack of depth and detail, however, so I’ll elaborate on each point:

Fascists are conspiratorial and irrational thinkers whose beliefs are rooted in emotions rather than facts.

Fascists are largely uninterested in nuance and complexity, preferring simple single-cause explanations for everything.

Fascists are distrustful of mainstream narratives and institutions, but place great implicit faith in the statements of their movement’s leaders, however groundless they may be. They easily accept baseless and false claims that support their worldview while doubting well-established evidence that contradicts it.

Fascists are anti-intellectual, disdainful of higher education, and suspicious of the arts. Professors and universities are frequent early targets of fascist movements.

Fascists are black-and-white thinkers, and they are unswayed by appeals to consistency. They conceive of their enemies as being irredeemably wicked, whereas their own entirely pure motivations act as justification for any of their actions. Their leaders are heroes, and any of their flaws can be excused or explained away; their opponents are demons or devils, and their every action is part of a grand conspiratorial plot against the nation and its people.Fascists claim to be defending the nation and its people from existential threats and working to restore a mythic past greatness.

Fascists believe that the nation is in decline and that its people are being degraded, and they are obsessed with restoring the nation to greatness through a purification of its people.

Fascists express a desire for revenge against those who have, in their view, betrayed the nation and its people; this group typically includes current or former political elites.

Fascists’ definitions of the nation and its people rely on racial, religious or cultural boundaries that invariably exclude some marginalized groups, who are part of the existential threat that fascists claim to be struggling against. These groups are “the enemy within”. They are blamed for the decline of the nation and become the target of fascist violence.The primary goal of all fascist movements is to constantly expand and consolidate power by any means necessary.

Fascists are not choosy about the tactics they use in amassing power; any action they take is permissible given the urgency of the existential threat they claim to be working against.

Fascists are happy to participate in the democratic process while simultaneously attempting to undermine it by claiming that its outcomes are invalid or manipulated against them.

Fascists are aggressively hostile towards leftists, scornful of liberals but willing to work with them when it helps them achieve their short-term goals, and entirely at ease accepting the support of conservatives and of the capitalist class.

Fascist regimes feel unconstrained by international treaties and conventions, often viewing these as part of a grand plot against the nation and its people.

Fascists’ willingness to engage in violence is proportional to their level of influence. In the earlier phase of their movements, fascists may try to present themselves as level-headed, reasonable, and open to debate. As their numbers increase, groups of fascists are willing (and often eager) to engage in street battles against their opponents. When in government, fascists expand police powers, target and imprison their enemies, and frequently find pretenses to suspend the rule of law and elections. At the greatest extremities of power, fascists commit genocides against the groups they have identified as existential threats to the state and its people.

What I hope to stress with this detailed description of fascism is the role of everyday fascists. When you picture a fascist, you probably picture Hitler, but Hitler was nobody without the masses of millions of ordinary Germans who supported him and spread his hateful ideas. Fascist governments are the result of fascist movements which gradually build support for atrocities through emotionally appealing lies. Fascism is not an ideology; it’s a process, and we’re partway through that process right now.

In some ways, Canada is in a fortunate position. On the same day as the Christie Pits rally, over 100,000 fascists gathered in London, England for a massive show of force. Speakers at the assembly denounced “the great replacement of our European people,” claimed that “we are being colonised by our former colonies,” and called for the mass deportation of Muslims. The world’s richest and most obnoxious man, Elon Musk, appeared by video link on massive screens to deliver a fifteen-minute hate speech, absurdly wearing a t-shirt reading “What Would Orwell Think”; he urged the assembled mob to overthrow the British government, asserting that “the left are the party of murder” and warning them that “violence is coming...you either fight back or you die.” A group of 5000 anti-fascist counter-protesters was entirely encircled by the fascists and trapped for hours behind police lines, unable to leave for fear of attack.

In their focus, the two events were identical, but the scale and outcomes were vastly different. The fascists in Toronto were heavily outnumbered by a large and celebratory anti-fascist crowd. The event had been heavily promoted on social media and through activist networks, and the turnout was impressive. There was an ice cream truck and a quesadilla cart, pride flags and hand-made signs and speakers and perhaps a thousand liberals and leftists willing to take a stand against fascism.

The initial crowd of fascists was chased out of the area by overwhelming opposition. They later claimed it was their plan all along to march to Yonge and Dundas, an hour-long brisk walk from their rallying point. Nothing in any of their promotional material for the event suggested anything about marching, so I suspect this was an impromptu decision in the face of an untenable situation – run away, regroup, and then return. They were hounded all the way downtown by anti-fascist counter-protesters.

When they did eventually attempt to creep back into the park, they were met again with loud and uncompromising opposition. “Go home, fascists!” we chanted. The fascists, predictably, misunderstood this straightforward description of their beliefs as a term of personal abuse; they replied with an echoing chant of “Go home, faggots!”

We don’t need fascists to agree with us or even understand us when we call them fascists. But we do need people who haven’t been infected with paranoid brain worms to agree with us and to use the label as well. Fascism in Canada is a growing problem, but it’s also not yet the same kind of deeply entrenched brain worm epidemic that’s afflicting countries like the US and the UK. If we want any chance of successfully confronting and defeating fascism in our cities and towns, we need to take the threat incredibly seriously, and an essential part of that is educating ourselves about what fascism is and calling it out whenever and wherever we see it.

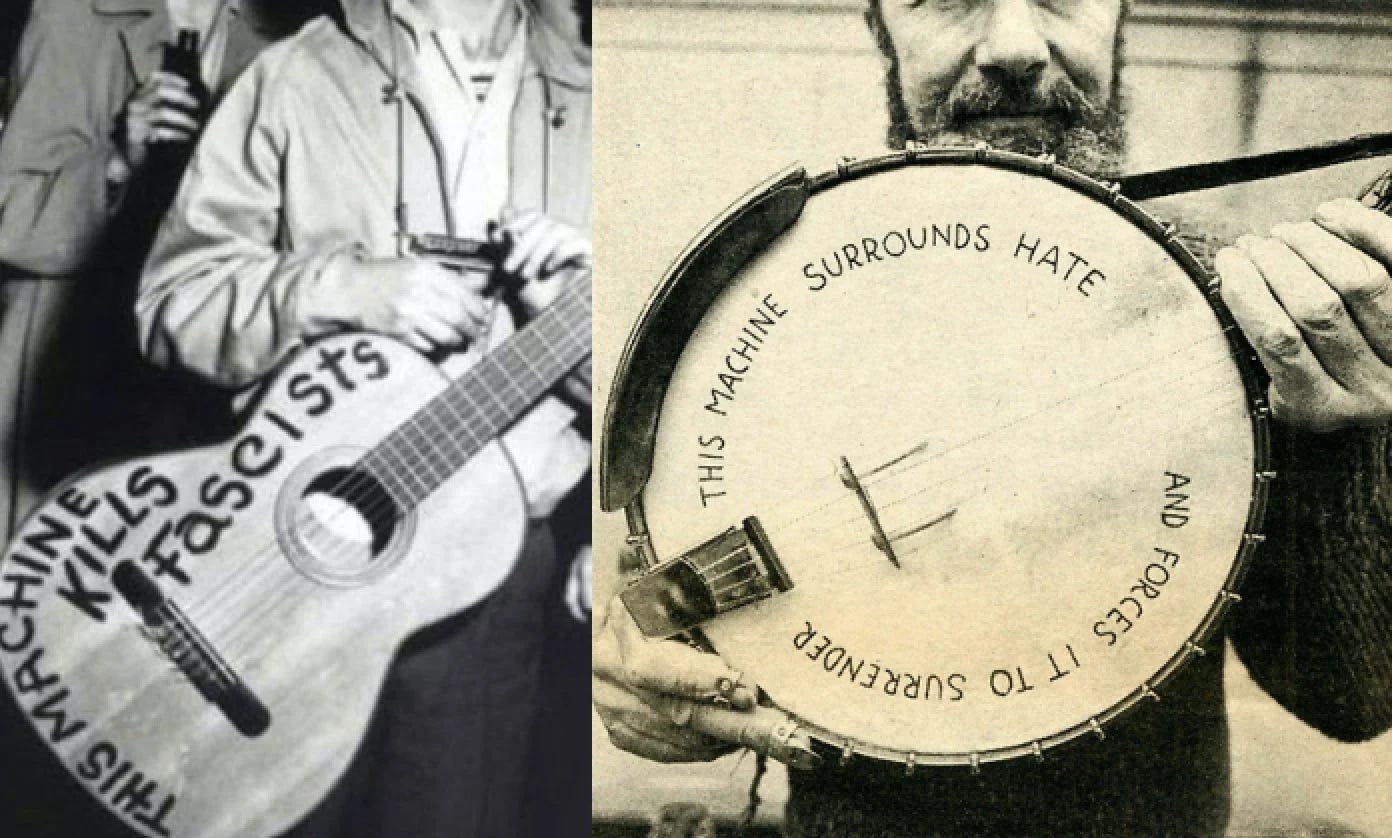

Shalom Auslander and Mike Godwin were quite right to see the misuse of “Nazi” and “fascist” as a profaning of something holy, the cheapening and trivialization of something monstrous. The flip side of this, however, is that when we see fascism, it’s imperative that we react as though people’s lives were in danger - because they are. “Fascist” is a dirty word, an irredeemably toxic label, and that makes it one of the most powerful weapons we have in the struggle against this vile movement. There is power in a name; let’s name the problem we’re facing so we can approach it with clear eyes and firm resolve.